In

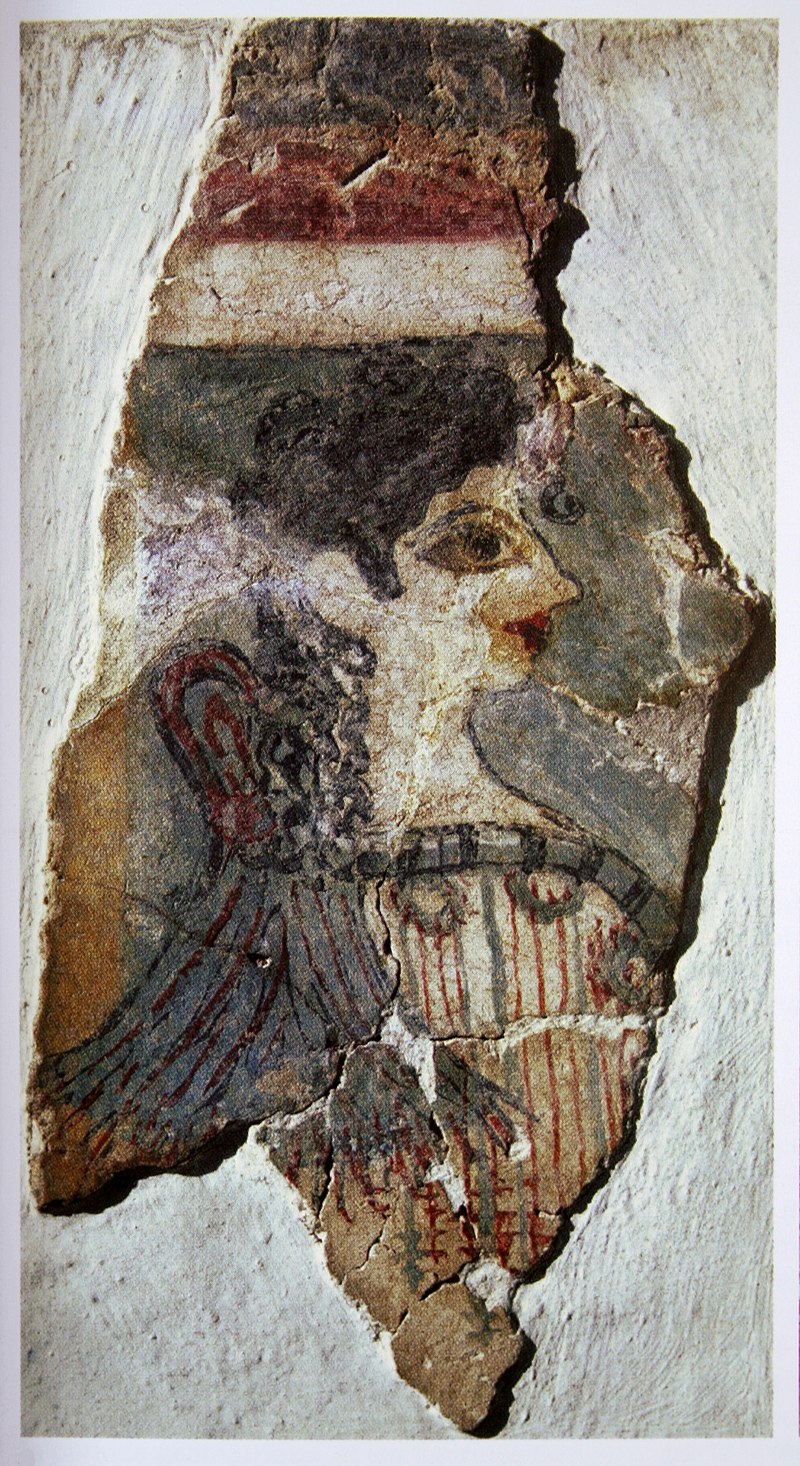

the eastern section of room 1 of the House of Ladies, two female

figures are engaged in an unknown activity. However, only a small

portion of the figure’s skirt and forearm remain.

The woman

depicted has rich, flowing black tresses and a red streak on the cheek.

She wears a gold ear-ring and a bracelet on her left arm. The position

of the arms made it impossible to depict a necklace. The figure is shown

bending forward at an angle of about 70°, so that her inordinately

large breast is exposed and hangs down from the decolletage of her

bodice. This lady’s feet also protrude from beneath her Minoan style

skirt. Again the position of the arms indicates that she is

participating in some activity taking place in front of her (east)

where, in the course of the reconstruction of the frescos, a fragment of

wall-painting probably showing part of the arm of another female figure

has been placed. Exactly below the surviving fragments of the arms of

the bare-breasted figure, is preserved part of the representation of

another Minoan skirt which creates a little visual confusion.

The most popular interpretation of this wall-painting suggests a

religious significance. An alternative interpretation is that this

wall-painting celebrates an important event in the life of the a

missing figure.

The frescoes of three elaborately dressed women were found in the

“Lustral Basin” of Xeste 3. They appear to be heading towards what

scholars have interpreted as an altar/shrine. The women’s rich clothing,

fine jewelry, and meticulous grooming indicate the social status and

importance of this composition.

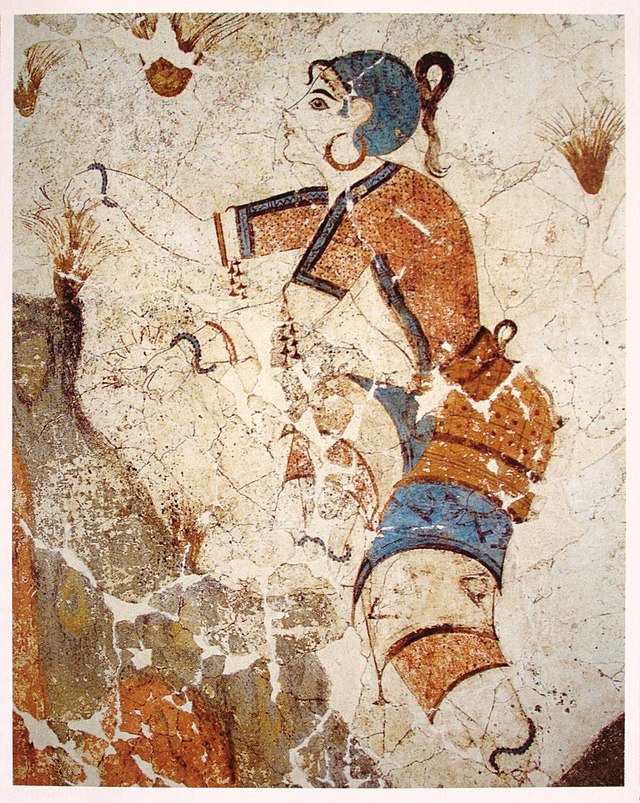

This replica shows the first figure from the left, the western most,

advancing towards the altar. In her left hand a necklace of rock crystal

beads. She is portrayed with her head in profile, her chest in

three-quarter pose and the lower body in profile. Her curvaceous body is

readily discernible beneath her transparent sleeved bodice, which is

embroidered with crocus stamens. As in many other Minoan frescoes, her

breasts are bared. Although the artist skillfully conveys the allure of

the female form through the transparent fabrics, he has some limitations

conveying the perspective of the right breast. This, like his Egyptian

contemporaries, depicts an elegant young female with just one breast.

Mini Papyrus Plants

Found in the West section of the House of Ladies, frescos of massive,

three stemmed, blossoming plants are painted on the walls. The lower

zone is painted in a reddish-yellow color with an undulating curve,

presumably an attempt at rendering uneven ground. The stems spring from

clusters of outwardly curving leaves and bear bell shaped flowers. The

stamens project above the rim of the flower. The colors used by the

artist in rendering the plants are black, blue and yellow. In the

repetitive motif, each grouping of the plants shows clusters of three

stalks surrounded by two triads of leaves and the fixed number of seven

stamens.

Dual Papyrus Plants

Found in the West section of the House of Ladies, frescos of massive,

three stemmed, blossoming plants are painted on the walls. The lower

zone is painted in a reddish-yellow color with an undulating curve,

presumably an attempt at rendering uneven ground. The stems spring from

clusters of outwardly curving leaves and bear bell shaped flowers. The

stamens project above the rim of the flower. The colors used by the

artist in rendering the plants are black, blue and yellow. In the

repetitive motif, each grouping of the plants shows clusters of three

stalks surrounded by two triads of leaves and the fixed number of seven

stamens.

The Saffron Goddess

The Saffron Goddess is a detail from a fresco depicting a saffron

harvest. The flowers are being picked by young girls and monkeys. This

Minoan goddess supervises the plucking of flowers and the gleaning of

stigmas for use in the manufacture of what is possibly a therapeutic

drug. Standing guard is a stylized griffin. The mythological griffin,

thought to be an especially powerful and majestic creature, was

considered to be a combination of the body of a lion as king of the

beasts and the head of an eagle as the king of the birds. Minoan

frescoes are the first botanically accurate visual representations of

saffron’s use as an herbal remedy. Minoans discovered the value of

saffron and there is enough evidence to believe that they were using it

to treat wounds. This theory is reinforced in another fresco from the

site which depicts a young woman using saffron to treat her bleeding

foot. (Fresco to come)

The Saffron Gatherer

The Egyptians had a limited number of colors that they used for their

murals. White, black, red, yellow, blue and green. The pigments that

were used were almost all manufactured from naturally occurring mineral

substances. The Egyptians later learned to create mixed colors from the

primary ones, such as grey, pink, and brown.

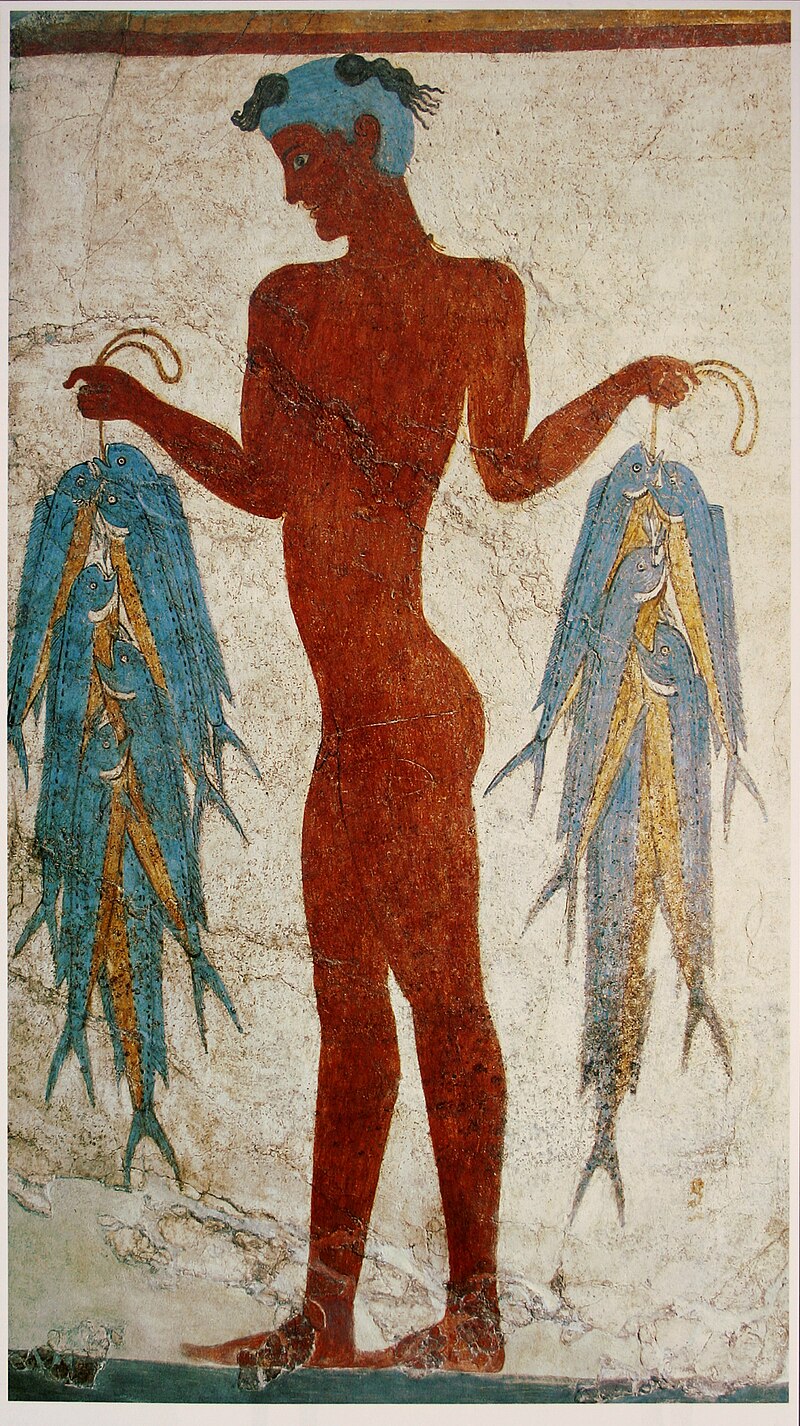

This replica shows two women are depicted in a field of crocuses. The

older figure (not shown) is gathering flowers with her right hand, while

holding a basket in her left. The younger figure, with the shaved blue

head, is gathering the stamens with both hands. The age difference,

manner of dress and the way they're interacting may imply that this

figure is a student. The Crocus grows even today on the Aegean islands

and mainland Greece. Saffron, which is derived from the stamen of the

crocus, has been used as a dye, a medicine, a spice and a perfume for

centuries. Saffron in Akrotiri likely used for the dyeing of robes.

Saffron-colored robes are found throughout the wall-paintings, mostly

adorning women. In Classical Greece, crocus dye was a symbol of

supremacy and wealth.

The ancient inhabitants of the island of Thera were quite aware that

they had built their city on a volcanic island, as evidenced in this

painting in the black and red volcanic stone and soil on which the girl

is gathering her flowers.

Since these plants are stylized, their actual identification

has caused much academic debate. Since the late 1960s, they have been

recorded as sea-lilies, sea daffodils or Papyrus. Sea-lilies still grow

on the beach and seaside of Santorini, blooming in late summer. But

recent studies have concluded that these flowers are more likely to be

papyrus. Not only do the Theran stylistic renditions of these flowers

have parallels in Egyptian papyrus imagery, but also evidence suggests

the existence of papyrus in Crete during the Bronze Age. Also, the

height of the flowers, which fill the walls, suggest a scale better

suited to a papyrus than to the much smaller sea-lily. Papyrus grows to

up to the scale of the frescoes and displays a symmetry equivalent to

the flowers in this wall-painting.

Since these plants are stylized, their actual identification

has caused much academic debate. Since the late 1960s, they have been

recorded as sea-lilies, sea daffodils or Papyrus. Sea-lilies still grow

on the beach and seaside of Santorini, blooming in late summer. But

recent studies have concluded that these flowers are more likely to be

papyrus. Not only do the Theran stylistic renditions of these flowers

have parallels in Egyptian papyrus imagery, but also evidence suggests

the existence of papyrus in Crete during the Bronze Age. Also, the

height of the flowers, which fill the walls, suggest a scale better

suited to a papyrus than to the much smaller sea-lily. Papyrus grows to

up to the scale of the frescoes and displays a symmetry equivalent to

the flowers in this wall-painting.

In Minoan society everything was

painted on: walls, floors, toys,

pottery, figurines, columns, and

even clothing, but sadly only 5-10%

of any given fresco survived. In

temples wood columns were painted

red, and stone friezes commonly show

rosettes. True frescoes are painted

on wet lime plaster, but Minoan

artists also painted on dry

surfaces. This was in stark contrast

to their Egyptian neighbors, who

painted directly on limestone or dry

gypsum plaster. Wall and ceiling

plaster was sometimes modeled in

relief, such as the spiral relief in

the north wing of Knossos, the bull

relief at the north entrance

passage, and the bull-grappling

fresco in the east wing. Frescoes

are found everywhere: in houses,

shrines, and in temples.

|

|

The Hall of the Shields at

Knossos

|

The origin of fresco painting is

truly in the neolithic and EM

periods. Important buildings during

the FN (final Neolithic) and EM

periods had their walls and floors

covered in plaster. This early

plaster consisted of lime mixed with

clay, and was sometimes colored red

or black, strikingly similar to the

conventions of Catalhoyuk's plaster

wall painting thousands of years

earlier in the 7th

millennium BCE. By the MM period,

around 1,900 BCE, Minoans began to

paint red and white geometric

patterns on temples, they used flat

washes on their temple walls. The

earliest true frescoes are from

around 1,700 BCE and the practice

flourished during the NT period.

Many early frescoes used dark red

prominently, and the color continued

its prominence through the NT period

as the color of the Knossian

palace's columns.

|

|

A diagram of the pigments

used in Minoan frescoes

|

By the MM period high purity lime

plaster and a greater variety of

pigments allowed fresco painting to

proliferate. The colors used in

frescoes came from a wide variety of

sources. Red and yellow came from

ochers, black from carbonaceous

shale or charred bone, blue from

copper tinted glass or ground lapis

lazuli. Green, pink, and grey were

created from mixing pigments, but

shading in light and dark was never

used. Minoans painted real figures

such as humans and animals, but not

everything was done in a strictly

realistic manner. Abstract swirling

geometric designs are intricately

incorporated into many frescoes,

most notably into the griffins in

the Throne Room at Knossos. Fresco

painting usually involved three

zones: repeating patterns above

windows or doorways, the main

composition in the center of the

wall, and dado at the floor level,

often imitating stonework.

|

|

A decorative frieze at the

palace at Knossos

|

|

|

Detail from that frieze |

|

|

|

Detail of a rosette on a

griffin in the Throne Room

fresco at Knossos. The

rosette is located on the

griffin's shoulder, it

should be noted that this

picture is upside down and

the flowers actually point

downward | | | |

|

|

|

Decorative rosettes from a

fresco at Akrotiri, on the

island of Thera

|

|

|

Detail of a fresco now in

Evan's reconstructed

“Gallery”

|

Animals are commonly found in

frescoes, especially monkeys.

Monkeys are always painted blue, as

was the Egyptian fashion, some even

wearing harnesses. Dolphins, fish,

and octopuses are common subjects.

People are often shown smiling.

While there are scenes of nature in

Minoan frescoes, they are often

exacted with an unrealistic

aesthetic strategy, and incorporate

a kind of abstract minimalism. The

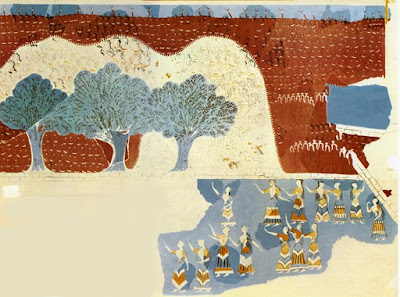

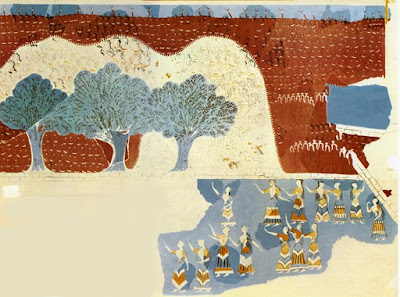

Spring fresco in Akrotiri shows this

design style, as flowers and birds

become a few interspersed brush

strokes. The background in the Blue

Bird fresco also exhibits this

aesthetic sense.

|

|

The Spring fresco in full,

at Akrotiri

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The lily fresco from the

storeroom of house X of the

southern area, Kommos,

Crete, Minoan

|

|

|

Detail from the Monkey

fresco

|

|

|

Blue Monkeys from the Beta

6 fresco at Akrotiri

|

|

|

The Blue Bird fresco from

the House of the Frescoes at

Knossos

|

|

|

The Blue Bird fresco in

full

|

|

|

Detail of the Dolphin

fresco at Knossos

|

|

|

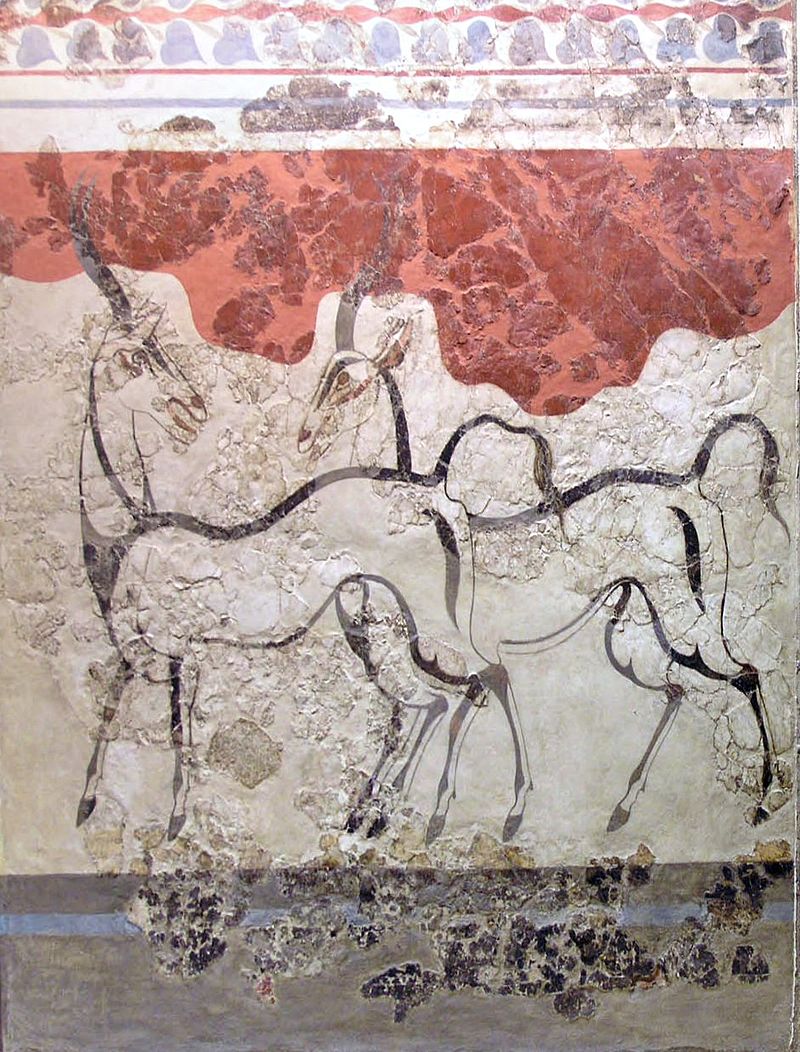

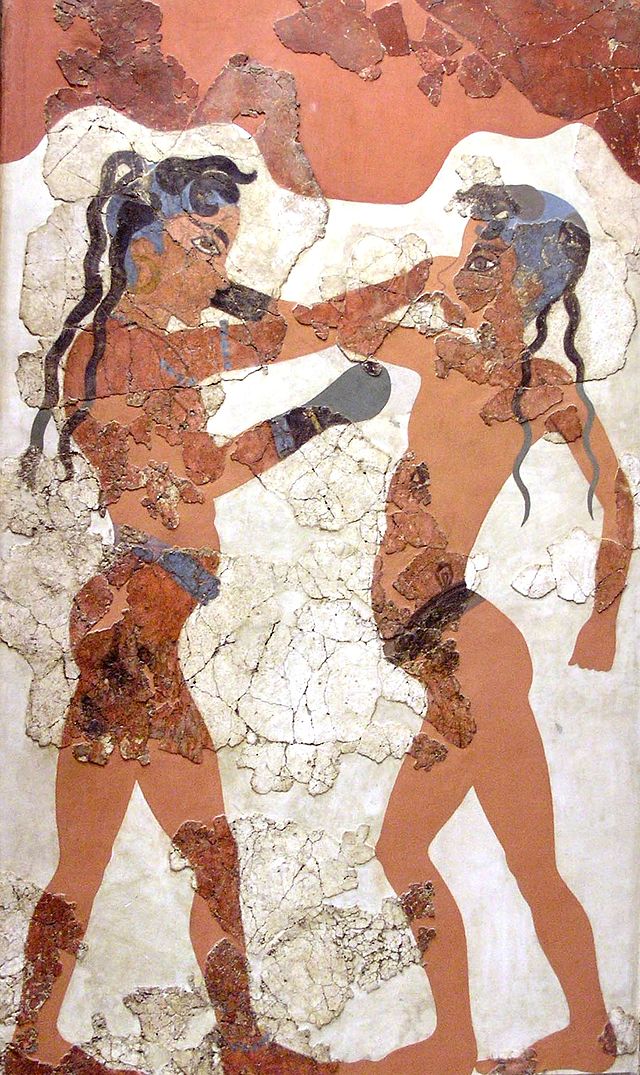

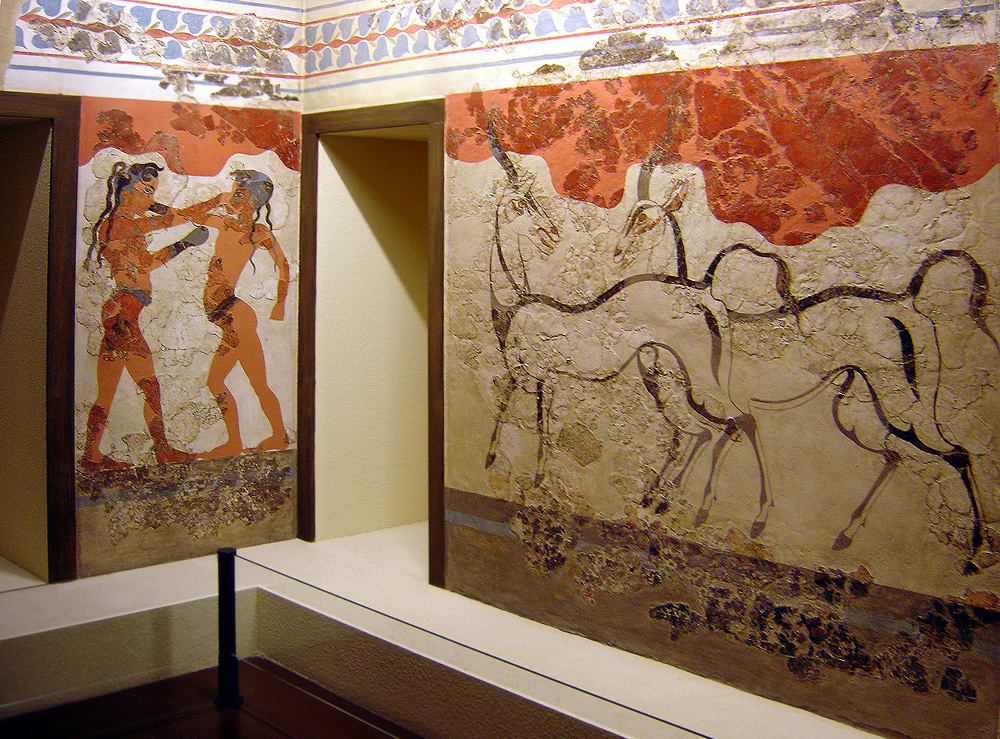

Minoan frescoes of goats

and the Boxer fresco at

Akrotiri

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A flying fish from a Minoan

fresco

|

Minoan miniature frescoes are

impressive, and from 1,700-1,400

Crete was the epicenter of Aegean

fresco artistry. The sizes of

frescoes ranged from truly tiny (a

few centimeters across) to life

sized humans. On the Procession

fresco in the Knossos labyrinth

fabrics are etched onto the figures

with a string, allowing for ultra

detailed lines and patterns. The

attention to extreme detail shows

itself in the intricately designed

clothing on the life sized frescoes,

such as the Cupbearer at Knossos,

and the elaborate Procession fresco.

The Villa of the Lillies at Amnisos

includes 7 zones of differing ocher

use with a decorative criss-cross

pattern.

|

|

The Cupbearer fresco from

Knossos

|

|

|

The Procession Fresco, this

picture is actually much

larger, please download it

and zoom in

|

When ceremonies are depicted in

frescoes, the priestesses are shown

bedecked in bright colors, and are

always central in the painting's

narrative. Forming a background to

the priestess foreground in such

frescoes is the crowd, the commoners

who flocked to such celebrations. In

the Sacred Grove fresco they are

drawn without individual identities

only represented as a repeating

pattern of bobbing faces lost in a

sea of dark red. This was partially

done out of necessity, as the entire

fresco itself is already a

miniature, making each face

extremely small and details neigh

impossible. The skill required to

make this miniature fresco is

astounding, and even with the size

constraints the artist managed to

create a pleasing and distinctively

Minoan aesthetic.

|

|

The Sacred Grove miniature

fresco

|

Arthur Evans assumed that Minoans

were great lovers of nature since

natural scenes are heavily

represented in their frescoes. This

wrongheaded stereotype of Minoan and

LBA Aegean culture is still somewhat

pervasive in modern society. In the

academic community much of Arthur

Evans' interpretation has been

debunked, Arthur Evan's

interpretation relies too heavily on

his own western sensibilities. When

Evans saw nature, he saw placid and

idyllic romanticism, and in doing so

overlaid his 19th century

world view onto the Minoan

world.

“...the roses on their tea cups

and the ivy-covered trellises on

their wallpaper would not blind us

to the Victorians' capacity to

exploit child labor and commit

acts of ruthless military

aggression in India and Africa.” - Rodney Castleden

|

|

The “sacral ivy” fresco

from the House of the

Frescoes, Knossos, from pg

67 of The Arts in

Prehistoric Greece, by

Sinclair Hood

|

Much of the Minoan's frescoes depict

not nature strictly, but show an

entire other world. As Castleden

puts it, they

“call down deities” as the

individual's experience of the

frescoes was entirely intertwined

with its cultic aspects. The

frescoes are brimming with meaning

lost now to humans today, a meaning

significantly more complex than

Evans' “reverence of nature”. The

plants and animals often depicted in

frescoes are in fact not natural,

but supernatural. Imaginary plants

are shown, curled into elaborate

spirals. Various plants which

bloomed at different times of the

year are seen in frescoes blooming

together, setting the whole scene

apart from a standard depiction of

the natural world. Otherworldly

Griffins are a common theme in

Minoan art but their intended

symbolic usage is also now lost on

us. They seem to always accompany

priestesses cementing their

connection between Minoan myth and

the real world. On the famous Agia

Triadha larnax (a clay sarcophagus)

a goddess is shown driving a chariot

pulled by griffons. There is no

explanation for what that scene

represents, but certainly it is

outside of the natural world and

depicts the realm of myth. Frescoes

are often used as symbolic

“signposts”, such as painting

processions in hallways in which

processions took place. It is very

likely that the minds of many

Minoans would have entirely

connected these frescoes to their

cultic activities. What did

priestesses think when they saw

frescoes of griffons, and what did

artists feel as they painted such

scenes? We sadly do not know.

|

|

Detail of the Griffin

fresco from the Throne Room

at Knossos

|

|

|

A wider shot of the Throne

Room at Knossos

|

What is not so clearly seen in

Minoan art is their darker side.

Bull sacrifices are not shown except

in one spot: on the Agia Triadha

sarcophagus. This lone depiction of

the funerary practices obviously

shows gore, with the bull on a

sacrificial table surrounded by

blood. There is a naval battle shown

on the north wall frieze of room 5

of the west house, which shows the

dead floating in the water and

soldiers dressed to kill with

helmets, spears, and shields. A

fresco from Akrotiri shows an altar

covered in the blood of recent

sacrifices, and the Boxer rhyton

includes one individual being gored

by a bull. These scenes of violence,

combat, and blood, are few and far

between and the vast majority of

frescoes do not show these gruesome

consequences of Minoan practices and

naval military dominance.

|

|

The sacrificial bull from

the Agia Triadha

sarcophagus

|

|

|

Casualties in the water,

from the naval battle fresco

at Akrotiri

|

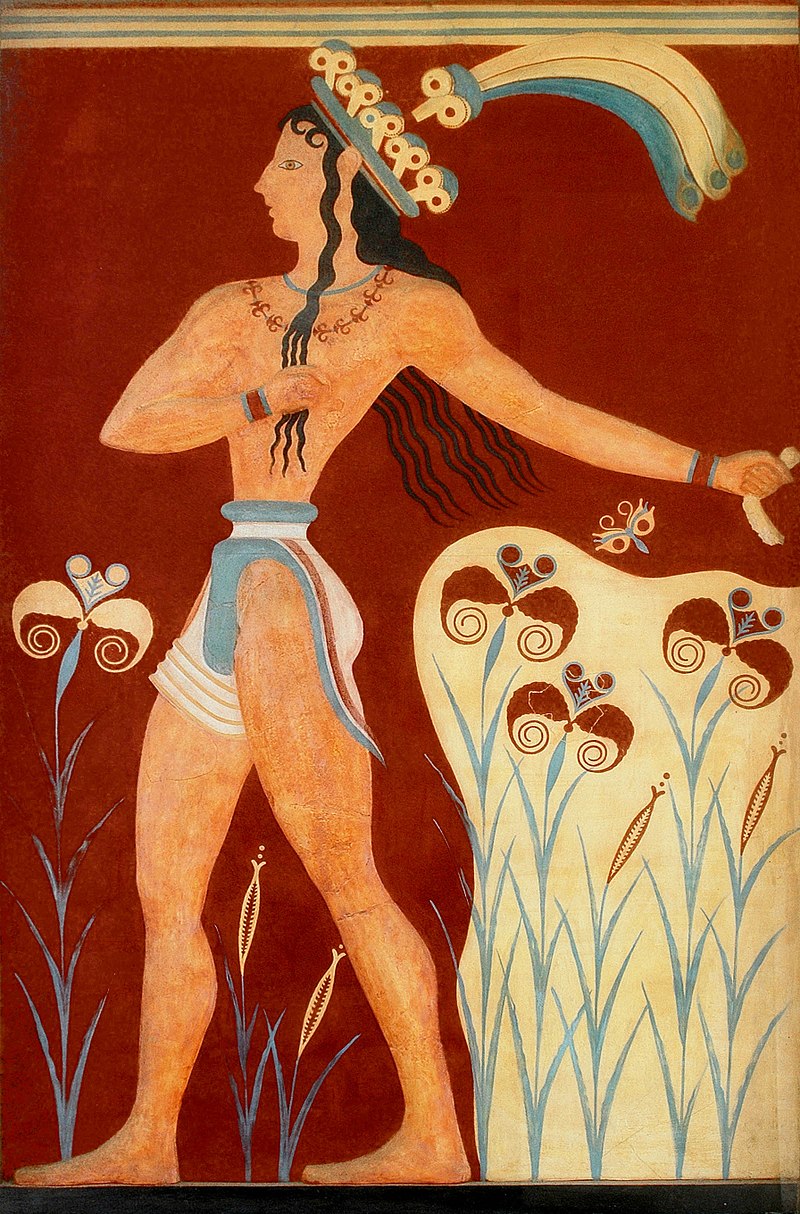

Minoan fresco art shows their

culture only insofar as they desired

to see themselves. Both male and

female figures are often physically

toned and proportionally beautiful,

wearing elaborate and form fitting

clothing. Minoan frescoes imitated

Egyptian frescoes and often painted

men in a rosy hue and women in a

whiter tone. Even as this is the

case, there is much ambiguity when

ascertaining the gender of figures

with some pieces (such as the Priest

King fresco) being neither red nor

white. The beautiful and sculpted

human figures seen in Minoan

frescoes were intended to grace the

halls and rooms of the rich, either

in their private residences or on

the palace-temple's walls. Workshops

by the Royal Road in Knossos also

include frescoes, and Akrotiri on

the island of Thera includes

frescoes in every building

excavated. The use of frescoes at

Akrotiri flies in the face of the

exclusive Knossian temple frescoes,

suggesting that frescoes were

incorporated into many class levels

and were brought into the daily

lives of more common people. This

liberal use of fresco art also

suggests that if the remainder of

the city of Knossos is explored one

would find frescoes commonly as

well, although it is possible that

each town would have had a different

relationship with its

painters.

Frescoes only show one aspect of

Minoan culture. Not everything was

included as a fresco or painted on a

jar, and even then what has survived

is only a minute fraction of the

whole. The complexity between

individuals and art, and between art

and symbolism, are both completely

intertwined with each other and

completely invisible in the material

record. It would be impossible to

deduce the complexity of 12th

century CE medieval society from

their stained glass windows, while

their existence speaks volumes about

the lives of those who lived at the

time, it does not tell the full

story. Also an interesting problem

to note is that an entire species of

crafted art (carved wood) has

completely disappeared. This is a

huge gap in knowledge, so huge its

total effective loss is unknown. It

would be similarly difficult to

truly understand medieval society if

by chance no stained glass windows

had ever been discovered.

.jpg)

|

|

Inaccurate reconstruction

from 1914 of a fresco,

attributed to Emile

Gillieron the son. Actually

the blue figure was a

monkey, the tail of which is

seen on the right

|

Minoan frescoes are not

only found on Crete, or at the

nearby Minoan settlement of Akrotiri

on Thera, but they are found around

the Aegean. Minoan style frescoes

are found on the Aegean islands of

Melos, Keos, and Rhodes, strikingly

similar to NT period designs.

Frescoes are also found outside the

Aegean, such as at the palace of

Yarim-Lim at Alalakh in Syria, where

a Minoan style griffin was painted.

A Canaanite palace at Tell Kabri had

a painted plaster floor and

miniature frescoes similar to the

ones found at the West House at

Akrotiri. Fragments of frescoes

found at the royal palace at Qatna,

Syria, show Minoan influence, such

as spirals, imitation stonework,

palm trees, and riverside scenes

with crabs and turtles. The most

spectacular Minoan frescoes are seen

at Avaris in Egypt, the capital of

the Hyksos dynasty of Egypt. These

frescoes show rocky landscapes,

bulls and acrobats, griffins, maze

patterns, half rosette friezes, and

one leaper has a Theran hairstyle.

It is entirely impossible to prove

whether these sites around the

eastern Mediterranean were done by

Minoans or simply by local artisans

copying Minoan styles. Either way,

the cultural dominance of Minoan

artistry was paramount across the

near eastern world, popular enough

to be desired by foreign rulers from

across the sea.

|

|

A scene of birds, a wall

painting fragment from the

Malkata palace made in later

reign of Amenhotep III who

died in 1,353 BCE. While

this fresco is distinctively

Egyptian, the upper border

of the scene is reminiscent

of Minoan abstract dados and

includes a repeating pattern

of rosettes

|

References

.jpg)